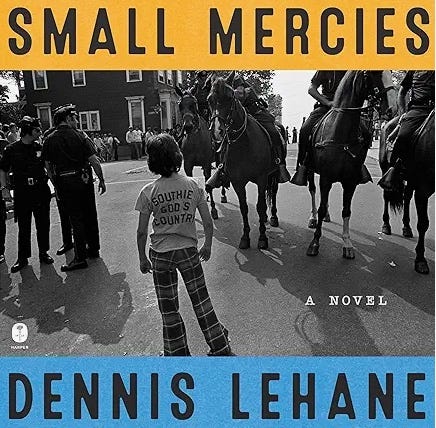

BookLife Review by Carol O’Day: Small Mercies: A Detective Mystery (Dennis Lehane, author)

Crime syndicate, South Boston, 1970s, school busing, racism, Irish-Americans, African-Americans, murder, violence, retribution, mother-daughter

Crime-infested, racism-rampant, whiter-than-snow, Irish-American South Boston (“Southie”) in the 1970s era of mandatory school busing is the setting of Dennis Lehane’s novel, Small Mercies: A Detective Mystery. Heart-broken and wizened, Mary Pat is our center. Her first husband, a career burglar, disappeared-died at the hands of Marty Butler, the local mob boss. Her second husband, whom she still loves, left her because of the “hate-infested” tone of her life and her neighborhood, where everyone other than pure and native Southies, and particularly the neighboring African Americans of Roxbury, were passionately and actively despised. She lost her beloed son to a post-Vietnam drug overdose and now her 17-year old daughter Jules has gone missing. The disappearance of Jules is so overwhelming to Mary Pat that she switches fully into fight and attack mode, a mode she has nurtured her whole life, and challenges even the local mob boss to find her daughter, and later to account for the disappearance.

To say that Lehane creates a character who is at-once gritty, wounded and sympathetic is to understate his talent. The reader simultaneously aches for Mary Pat, squirms at her racism, and fears her angry explosive action. Lehane’s Southie landscape is a thinly-disguised recounting of Whitey Bulger’s reign over South Boston in the 1970s but it is nonetheless gripping. It is a bit of inside-Hollywood and how-the-sausage-is-made. The reader enters the crime-invested world of protection syndicates, drugs, guns and murder as a method of terror and compliance. No one crosses the boss, and lives to tell about it. Moreover, anyone who poses a threat, including drawing attention of the police not on Butler’s payroll, or knowing too much about the boss’s doings, is forever silenced as well. Mary Pat dares to challenge that hierarchy because she has nothing left to lose.

The reader wonders if Jules is alive or dead, and what she saw, or did, in the headline-grabbing death of a young black man, Augustus Williamson, at a metro station where Williamson is found dead one morning under the train platform after encountering white teens the prior evening, the evening Jules goes missing.. As the drama unfolds, Mary Pat learns more and more of Jules’ secrets and becomes more and more bold in coercing information out of both teens and mob players. She commits perhaps the cardinal sin when she meets, however guardedly, with a local detective.

Gritty, appalling, riveting, and shockingly true to life, Lehane lays bare the overt and shameful racism and hatred that surrounded the controversial decision to bus students from Southie to Roxbury and Roxbury to Southie. The legal decision, in hindsight, was perhaps a misguided effort to level the educational playing field, while leaving the affluent, aka largely white, suburbs out of the equation. Southie mobilized to protest the integration of the schools and even insisted that its children boycott school rather than attend high school with black students from Roxbury. Lehane humanizes the African-American community by casting Augustus Williamson as the son of one of Mary Pat’s co-worker aides at the nursing home. Mary Pat does experience occasional misgivings and a latent conscience about the attitudes of her community, but her beliefs are so baked in that she cannot shake them entirely; there is no viable infrastructure of support for behaving or believing anything other than as she does as a born and bred Southie native, a lifelong inhabitant of the housing projects.

Mary Pat’s conduct is violent and abhorrent, and she exercises her wrath on teenagers and adults alike. And yet, the reader somehow understands on some level and roots for her against the mob. While this may be a bit of a trope, bad conduct makes sense against greater evil, Lehane does enough to humanize Mary Pat to make it palatable, and even compelling at times. It becomes an unstoppable train of destruction and reads like a film. While this story may well appear on the screen in the future, Small Mercies is nonetheless a good read while we wait to see who will be cast in these juicy roles.

Support local bookstores and BookLife: Reviews for Readers by purchasing Small Mercies using the link below: